FROSTPUNK 2 IS A VIDEO GAME ABOUT SOMETHING

the city must survive.

We survived the end of the world. Now what?

That question is the thumping engine that drives Frostpunk 2. As the Steward of New London, a fledgling city forged by survivors of a winter apocalypse, the power to build that future is in your hands. The city is growing rapidly, and resources are depleting just as fast. The way you handle these crises will shape the world that emerges from the snowy ruins. Will you embrace the new reality of blizzards and the struggle for warmth? Or will you cling onto the old world’s hunger for innovation and attempt to preserve what was lost?

The original Frostpunk is not a game I played much of, petering out in its opening hours after feeling overloaded with information—an onboarding problem that most strategy games face. But the game always caught my interest from afar. Frostpunk won Polish developer 11 Bit Studios a slew of prestigious awards and a BAFTA nomination, and as a longtime fan of grand strategy games, the idea of one focused on narrative was interesting. My excitement for Frostpunk 2 reached a fever pitch after reading Polygon’s recent interview with co-director Jakub Stokalski which made it clear this isn’t just an attempt to capitalize on Frostpunk’s success, but is a project 11 Bit Studios embarked on because it had a compelling creative vision that it wanted to communicate.

That vision was to create an intensely political game that makes the player question at what point they’re willing to compromise on their ideals—something no other game I can think of has forced me to reckon with.

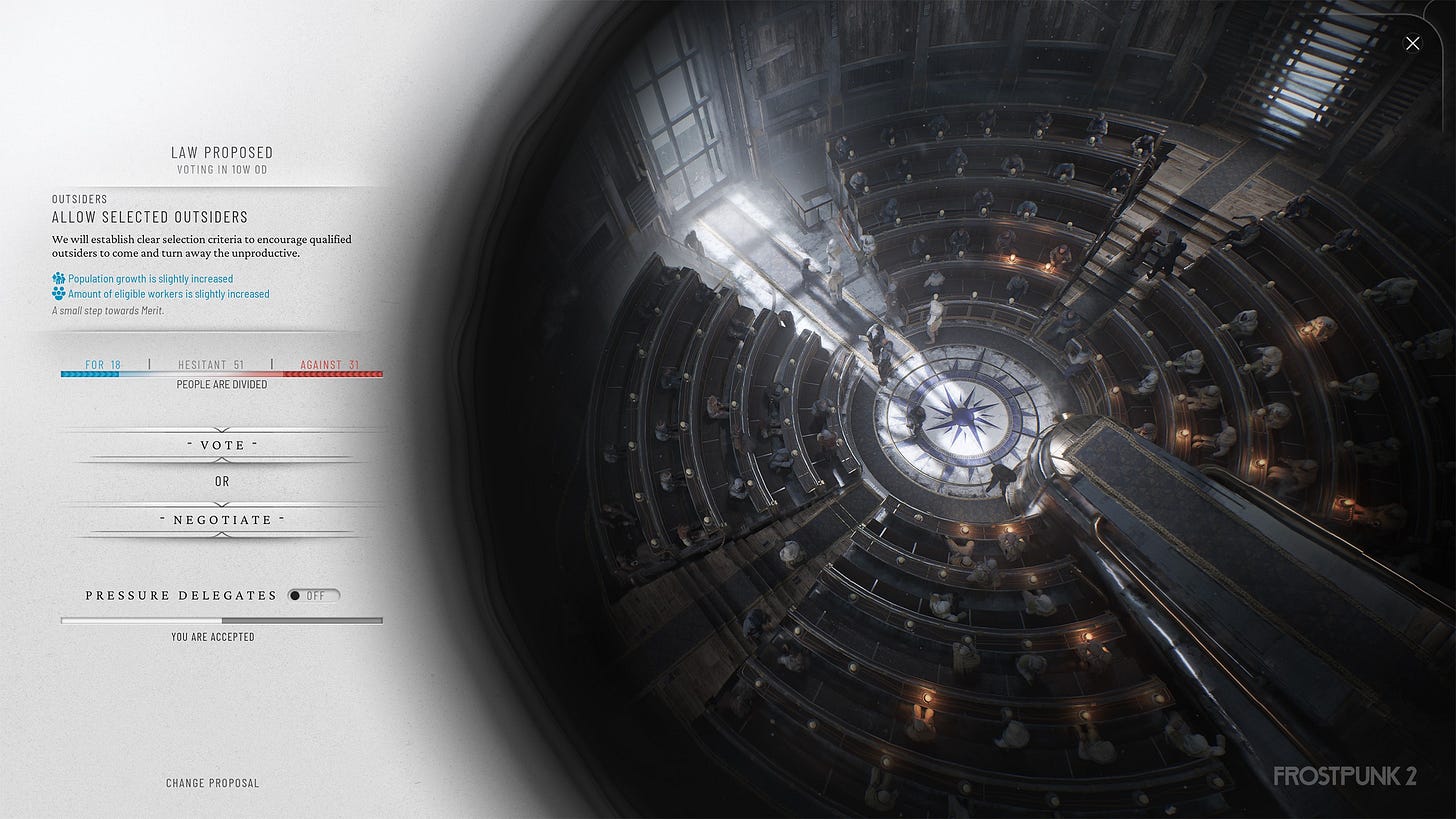

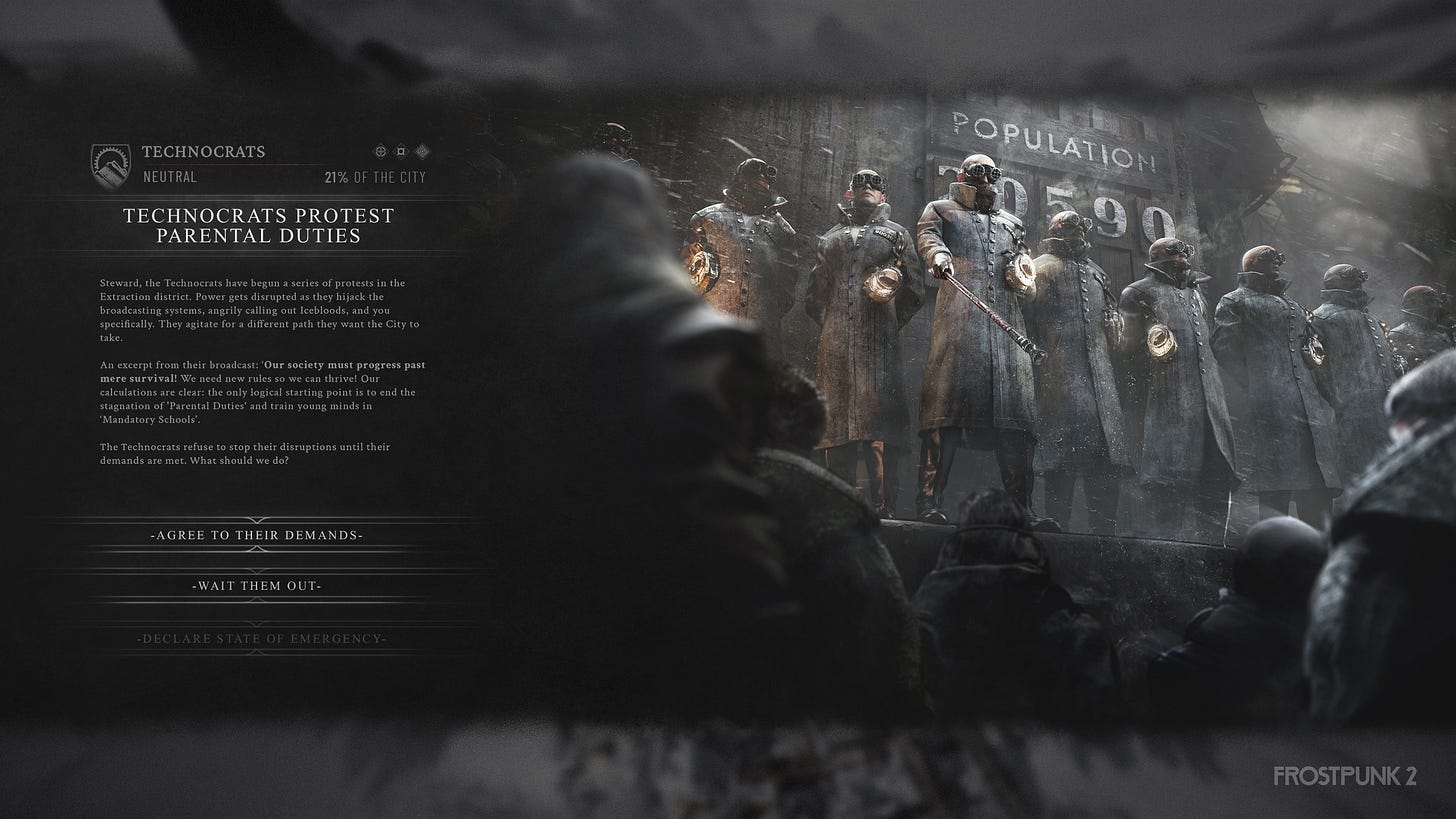

This is still a survival game: You’ll spend most of your time in Frostpunk 2 building districts to expand New London and searching for an ever-diminishing resources to sustain your population’s needs. But politics complicate that basic layer of management. The Captain, the player character from the first game who helped build New London, has died, and a parliamentary council system with the player’s Steward at the helm has replaced their monolithic lead. In this council, different factions vote on policy proposals and battle to influence New London’s direction. Whatever utopic dream you want to carve out for the city will be muddied by the constant struggle for resources and need to satisfy the factions, who will only grow more extreme the longer you neglect them. Brush the traditionalist Frostlanders aside, and a more extreme faction will splinter off in the fiercely conservative Pilgrims, who could grow to become a much more significant thorn in your side.

I like a story that can ask “would you enact child labor laws if it meant survival?” But I love one that reaches up into that rarely touched top shelf of questions. Would you force the sick to wear badges to prevent the spread of disease? Should you let parents accompany quarantined children? Would you institute mandatory romantic partner rotations to increase a rapidly dwindling population? Should all outsiders be welcomed in, resources be damned, or only those who can contribute to the workforce? Should school be mandated for all youths? Should you frack to access more oil even though it will create smog? Or should you use water pressure at the risk of polluting the drinking water?

I’m a person who feels incredibly clear and strong-willed about my political beliefs, and you may find yourself skeptical at the idea that any of those questions would be tough choices. But Frostpunk 2’s deeply interconnected politics, resource scarcity, and city building adds a suffocating layer of complexity to every decision that challenges your ideals at every turn. Few decisions will please all of New London’s competing political factions, and tough conditions will force you to make gut-wrenching compromises for the sake of survival. I’ve never had a game challenge me quite this way before.

It’s not just the big-ticket political decisions in Frostpunk 2 that will have you massaging your temples. Every decision is utterly grueling, even smaller-scale ones like deciding where to construct new districts. At one point, after taking in refugees that significantly added to New London’s population, I was forced to build housing next to a coal mining district, fating its inhabitants to an ashen life under oppressive industrial smog. But it was the last bit of space left in the canyons where the homes would be sheltered from the frostlands’ harsh winds. It may be a squalorous existence, but at least it’ll be a warm one.

The question of whether or not video games are an art form is settled. They are. But despite the tens of billions of dollars being slipped into Big Boy Pants pockets at the industry’s highest corporate board rooms, they’re still a young one. Games have yet to have a Do The Right Thing or 1984 moment that sparks a meaningful debate in culture. Large-budget productions in particular are so consumed with player empowerment that droves of mouth breathing gamers think politics have no place in the medium, and that acknowledging the existence of women (or god forbid, a black woman) is too extreme a political statement for their audiovisual toys to explore. Frostpunk 2 is no Do The Right Thing, but it’s a miles-long leap in the right direction compared to other games in its genre.

Civilization is the poster child of the strategy genre with a history nearly as old as computer games themselves, but it presents history through rose-colored glasses. Sure—you can play as the Mayans or Iroquois and carry them from the ancient age into the future, sparing them from brutal annihilation. But they’re still forced to walk there down the same path of “progress” as the Western nations that includes colonialism, espionage, and nuclearization. Take the Mayans into the 21st century and their cities will be visually indistinguishable from those of the US or Germany. In recent years Civ has released expansions adding dark ages and climate change to its games, testing the waters of acknowledging the harder-to-swallow parts of human history. But it hasn’t stuck the landing: Climate change in Civilization VI can easily be shrugged off, and going through a dark age increases your chances of transitioning into a golden age. I don’t mean to do some epic takedown—I love Civ, and it’s fine that it’s more interested in gamifying the real path of world history instead of imagining an alternate reality. But by refusing to meaningfully interrogate history and presenting itself with a gilded, “look how far we’ve come!” attitude, Civilization ends up accidentally endorsing the worst elements of our history.

Paradox Entertainment’s Crusader Kings series is a step closer to what Frostpunk 2 accomplishes. That game uses a veneer of historicity to poke fun at feudalism, letting you falsify claims on land and eventually turn your family line of carefully inbred sociopaths into God-kings. But it’s easy to critique feudalism with several centuries in the rearview. It’s harder to create a meaningful examination of our current world order. There is room in this genre for so much more.

That’s where Frostpunk 2 excels. The game isn’t just a brutal self-examination, but also one that asks the player to imagine what’s next—where do we go from here, and which of our current ideals are worth preserving? You’ll rarely read a review of games like Civ and Crusader Kings without a mention of their “one-more-turn” addictiveness and ability to keep you playing for hours on end. But Frostpunk 2 is able to create that same stickiness by presenting you with an endless string of brutally stressful situations that challenge your imagination and deeply held beliefs in surprising ways. I found myself unable to tear myself away from New London, eager to see how my decisions would shape society and what problems I’d be presented with next.

The best compliment I can pay to Frostpunk 2 is that it feels obvious. It shows that strategy and management mechanics are perfectly suited to this sort of grand thematic statement, and games that don’t explore that narrative potential look weak by comparison.

Some of Frostpunk’s policy decisions are made all the more painful by its setting. The great blizzard hit in the late 1800s in Frostpunk’s Earth, so much of the medical and technical knowledge we have today isn’t available to the citizens of New London. One policy you can enact is to insulate homes from the cold with asbestos. It is a rare policy choice that appeases all of New London’s warring factions and increases the city’s warmth… but it’s also asbestos. The player might know that asbestos is an extremely dangerous carcinogen, but the Steward and the citizens of 1918 London sure don’t. For them, insulating homes at a relatively low resource cost to score a big political win is probably a no-brainer. But when we click the GIVE THEM ASBESTOS button, we know we’re dooming our residents to shortened lifespans and cancer. Moments like that are when the ability to immerse yourself as the Steward begins to crack a little bit, but it’s also a fascinating, gripping moral choice that exists outside the game space.

Frostpunk 2 reveals its own politics in subtle ways, but doesn’t put its weight on the scale. You can, of course, be delightfully evil in this game, politicking to increase your own power until the council is forced to make you Caesar. You can embolden the cops and install prison towers to keep crime in check, force marriages, force elders to death march into the frostlands, and more. It begs playing and replaying to explore different policy outcomes and strategies for growing the city. There may be benefits to letting the cops chase down criminals in the streets… but is that the kind of society you want to create? Mess up badly enough, and you may have to embolden the cops in order to prevent the city from utterly collapsing, unleashing a force you may never be able to put back in the box.

Frostpunk 2 is not doggedly devoted to depicting real world politics; it is still a video game, and is prone to bouts of amusing gaminess. Your industrial districts can be set to produce one of two things—prefabs that are used for construction, or goods that improve citizens’ quality of life. If goods production doesn’t meet demand, New London’s crime rate will increase significantly. But you can flip factories back and forth between prefabs and goods at no penalty, effectively giving you a CRIME ON/OFF lever to pull when things get dicey. Another amusing wrinkle: As soon as your population ticks up with the latest batch of births, your available workers will increase as though the previous batch of babies has already joined the workforce. The children yearn for the mines. There will always be seams where the game ends and reality begins to reveal itself, and since Frostpunk 2 explores such a rich idealogical space that other games don’t, it’s hard to complain about its unavoidable, accidental comedy.

Some tougher-to-get over seams are when you’re forced to make choices without clear enough information—or when you’re not even aware you’ve made a choice at all. You will sometimes find yourselves in situations where you must promise to research or enact a certain policy to appease a political faction, only to find that in doing so, you’ve cancelled out a previous policy, leaving an entirely different faction upset with you for reversing existing law.

Unfortunately, Frostpunk 2 is a fairly buggy experience. Pausing the game (which you’ll be doing a lot to make decisions without time stress) breaks its countdown timers. I encountered a bug several times that caused my frostland exploration teams to never return from their outings, freezing (hah) my progress and forcing me to reload saves from hours earlier. Hopefully these issues get ironed out with time and with player mods, but it has to be acknowledged. Frostpunk 2 is an incredibly ambitious project, and it sometimes feels like it’s shaking under the weight of its own mission like a generator that’s about to blow.

Frostpunk 2 approaches complex political questions with remarkable empathy. You can see the pain and woes of your citizens represented numerically constantly, but the game adds a human touch by showing city chatter that reflects the state and concerns of the population. Political factions are also treated with respect—not always for their ideas, as with the highly conservative Pilgrims, but for how their lived experience shaped them. The Pilgrims became so conservative because they survived the harsh cold wastelands as family units before arriving in New London, sleeping as one mass of bodies under blankets and rocks. You can see how that might create a culture that would place family cohesion above all else. They support the policy of allowing parents to accompany children in quarantine. They’re also in favor of Dedicated Motherhood—a policy that frees mothers from the workforce, but at the demand that they focus only on parenting.

Policy decisions in this game often have measurable impacts, but some choices present philosophical questions with uncertain outcomes. In New London, bodies are harvested for organs upon death, then cremated and their ashes returned to their families. At one point, the Stalwarts (effectively the Cop faction) suggest that we store frozen bodies since the rapid pace of technological advancement could mean we can one day find another use for them. So what should you do: Freeze the bodies and potentially upset the citizens? Or continue with cremations? And more importantly, what kind of culture would these policies create? Those more uncertain outcomes contribute to Frostpunk 2’s thick, oppressive mood.

Art direction also contributes. In this world wiped out by blizzards, life still thumps: New London’s districts course with an almost electric blue energy from afar, turning blood red when the city starts to fall into chaos. Citizens’ faces appear like mirages in plumes of smoke and pools of oil, which take on almost a religious significance in this world consumed with staving off the cold. Zoom in on any of your districts, and you’ll get to see a diorama of life that reflects the city’s current state.

But the star of the show is composer Piotr Musial’s score. Quivering strings evoke snow flurries and blizzards, while horns and cello provide a menacing, warm undercurrent like the oil that courses below the frozen Earth. Musial’s soundtrack bursts to the foreground at tense inflection points to highlight the drama. It’s at once triumphant, tragic, foreboding, and hopeful, reflecting the myriad paths this society can take as you steer it through crisis after crisis.

Frostpunk 2 is an experience that shouldn’t be missed by anyone curious about the future of video games. It’s a lodestar for what games could be but so often aren’t, even if it struggles to hold its own weight at times. It’s compelling, twisted, throbbing with life, and has consumed my imagination.

This game’s mission statement is laid clear on its title screen. The streets of New London ablaze in an open riot—or perhaps an industrial machine exploding the earth—is reflected on the goggles of a citizen, who stands gray against an oil-black background. Their hot breath rises from out-of-frame past the goggles’ fiery reflection. A society whose inner world is rapidly expanding. Almost imperceptibly, flurries of snow fall across their face—a reminder that whatever shape this society takes, it will never be free from the harsh reality of the world around it.